Lebanon: more water, less tensions

Since 2019, Lebanon has been experiencing a severe economic crisis while simultaneously hosting approximately 1.5 million refugees from Syria. Access to clean drinking water for all is not guaranteed, exacerbating tensions. In the Bekaa Valley, the SDC is running a project that utilises digitalisation and solar energy to improve water management. The project also aims to ease tensions surrounding water access. This initiative is part of Switzerland's broader efforts to address water-related issues in Lebanon.

The SDC has restored the Fekha water pumping station, which now runs on solar energy. © SDC

The Bekaa Valley is situated between two mountain ranges, with an average altitude of 1,000 metres. Spanning 120 kilometres in length and 16 kilometres in width, it comprises 42% of Lebanon's surface area. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that in 2023, the valley's population will be around 1.5 million, including one million Lebanese citizens. The remainder of the population consists primarily of Syrian refugees and approximately 8,000 Palestinians. It is worth noting that estimates of the number of Syrian refugees vary depending on the source, with some figures reaching up to one million.

Lebanon's population growth in the wake of the Syrian crisis, combined with a severe economic crisis, has exacerbated tensions over access to water. The Bekaa Valley has seen an increase in attacks on water supply infrastructure. Illegal connections to the water network have increased, as have disputes between water users.

Digitalisation and real-time data

It is in this complex environment that the SDC is conducting a project to promote equitable access to drinking water. In collaboration with the Bekaa Water Establishment, the SDC is working to improve water management and infrastructure. Since its inception in 2015, the project has successfully sought to alleviate tensions between communities and has achieved numerous significant accomplishments.

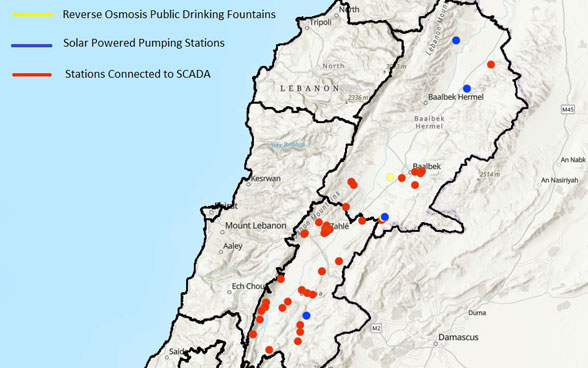

First, in the area of digitalisation, the 50 largest water stations have been connected to a centralised data centre. Thanks to the installation of sensors and 4G technology, this centre can analyse data such as water levels, flow, and pressure for each station in real time. The Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system, as its name suggests, can also be used to set minimum and maximum water distribution levels and regulate pumps remotely. This system now covers most of the Bekaa Valley, serving approximately 700,000 people.

As Andres Devanthéry, a water and sanitation specialist from the Swiss Humanitarian Aid Unit in charge of the project on site, explains, the data collected by the centre enables accurate monitoring of water consumption. "Some of the valley's inhabitants have been complaining to the municipal authorities, accusing them of supplying more water to certain communities to the detriment of others. With this data, we can objectively demonstrate how much water is consumed where and how often," explains Devanthéry.

The system also enables strategic decisions to be taken about infrastructure maintenance. "Thanks to the data at our disposal, we can monitor the performance of specific pumps. For pumps that show signs of age, we can schedule preventative repairs. In other cases, the pumps are so outdated that repairing them would require expensive work. When you consider that replacing a single new 100 kW pump costs up to USD 20,000, it is essential for the municipality to have reliable data to know whether or not the investment is worthwhile," says Devanthéry.

Solar energy as a solution to electricity shortages

The installation of solar panels on infrastructure is another key breakthrough achieved by this SDC project. In 2019, SDC was at the forefront of utilising solar energy in water projects. A few months later, Lebanon plunged into an economic crisis that continues to this day. Since then, nationwide power cuts have negatively impacted all aspects of daily life, including water access. "Much of the water supply is drawn from aquifers. Without electricity for generators, access to water ceases," explains Ramzi Ibrahim, a project engineer who works alongside Andres Devanthéry at the SDC office in Zahle, in the heart of the Bekaa Valley.

Ibrahim points out that installing photovoltaic panels at water stations has allowed some areas to extend their electricity supply from one to seven hours a day. We targeted areas at risk of water-related conflicts, often due to the local topography. For example, in the town of Fekha, a waterfall benefited downstream residents with a continuous water supply, thanks to gravity. In contrast, those upstream expressed their frustration at the lack of electricity for pumping water. Fekha's scenario is not unique in Lebanon, and our photovoltaic solutions have addressed this issue, showcasing the lasting impact of clean energy," says Ibrahim.

Water at the heart of disputes and tensions

Preventing water-related conflict is another priority of the SDC's project. Amal Abou Hamdan is a specialist in this field and a member of the SDC's team in Zahle. She maintains that decisions should be grounded in a thorough analysis of potential tensions. "We carry out studies on the local context, needs, and decision-making power regarding water use, which vary from village to village. Sometimes, water is diverted for agricultural use at the expense of drinking water needs," Abou Hamdan explains.

In Lebanon, water supply can depend on political or religious affiliations. The Bekaa Valley is a religious mosaic, with large Shia and Sunni Muslim, Christian, and Druze communities. "We organise public meetings with each community and individual meetings with their leaders. The main goal is to pinpoint potential sources of tension related to water use, understand each community's reality, and clarify water consumption issues. We show them the consumption and flow data collected by the sensors installed at the water distribution points. They are aware that our recommendations are based on reliable data that is not politically, religiously, or ethnically motivated," adds Abou Hamdan. All communities benefit from the SDC's interventions.

Abou Hamdan also raises awareness among her colleagues. "Proposing cutting-edge technical solutions is one thing, but if your project is perceived as a threat to a particular group's interests, it has no chance of succeeding. Installing solar panels on an agricultural field is no trivial matter. We've experienced resistance from landowners against solar arrays on their property. You might also face opposition from those feeling left out of your project. This can happen, for example, if you commission a service provider from one village to carry out work on a water station in another village. You therefore need to spend a good deal of time talking things through and dispelling doubts and fears. Awareness of conflict risks must be raised at all project stages, from contracts to logistics," Amal concludes.

Raising awareness about infrastructure maintenance and best practice for water consumption is also essential. Given Lebanon's high cost of living and unequal access to water, preserving existing resources is crucial. As part of the project, the SDC has supported awareness-raising campaigns run by young people in Lebanese schools. In Baalbek, another town in the Bekaa Valley, the SDC supported an initiative led by the town's young people to harvest rainwater. The treated water is accessible to all residents of a disadvantaged district of the town.

The results of the SDC's project in the Bekaa Valley have not escaped the attention of the Lebanese authorities.They are encouraging other donor countries and international organisations to emulate their example. The deployment of solar panels and the use of digital data for water management are being expanded to other Lebanese regions facing similar challenges.

The SDC plans to extend its solar energy programme through a novel approach that combines solar energy with hydrogeology and has already proven effective in Africa. This method guarantees simultaneous optimisation of water and energy resources, in keeping with the SDC's constant commitment to innovation.