"Rather than a Swiss or Roman initiative, informal diplomacy seemed more European in nature"

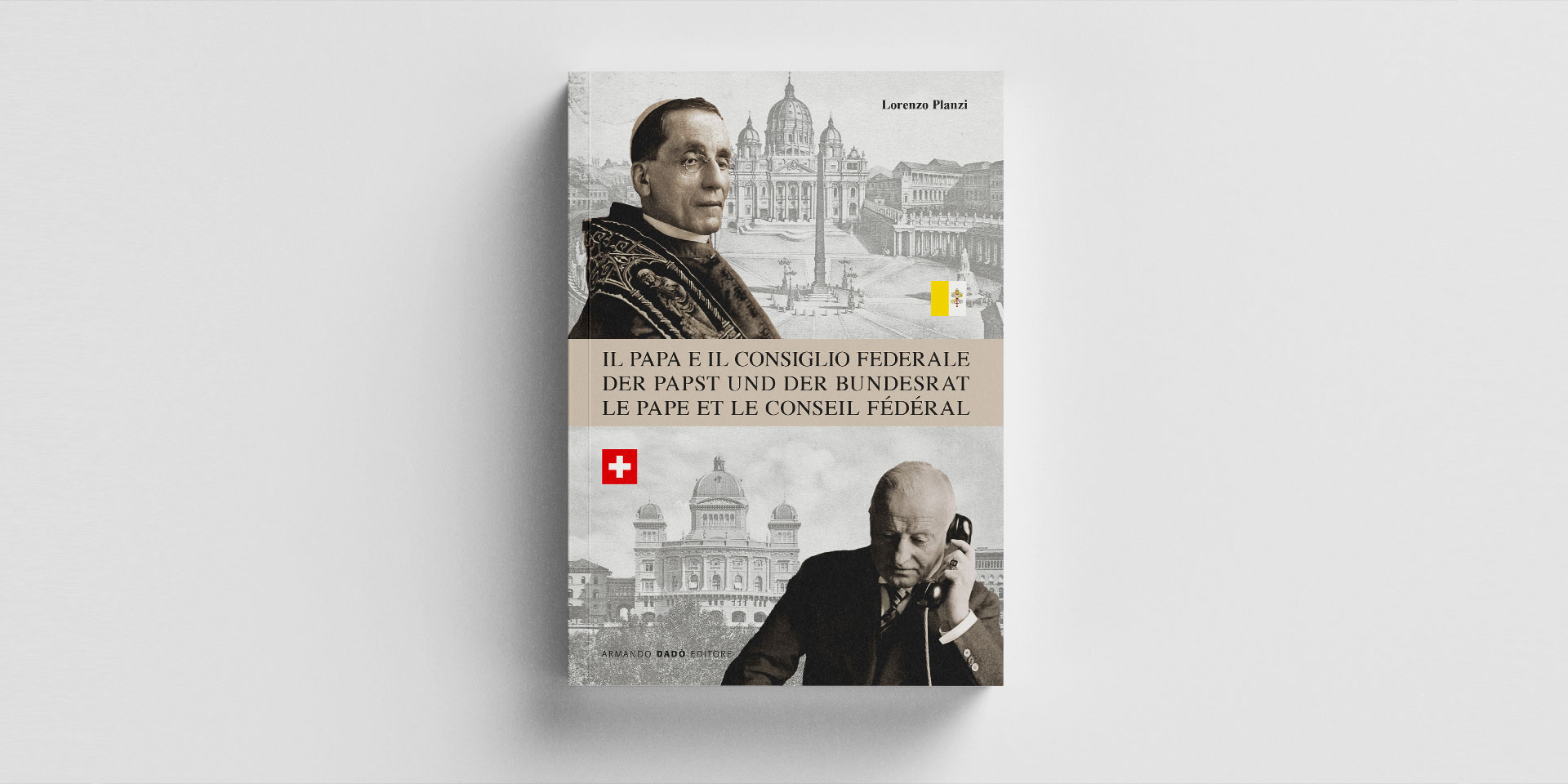

Following a break of almost 50 years, Switzerland and the Vatican resumed diplomatic relations in 1920. In his book "The Pope and the Federal Council", historian Lorenzo Planzi writes that one of the reasons for the rapprochement was the joint commitment during the First World War providing aid to captured German and French soldiers suffering from illnesses.

Switzerland and the Vatican broke off diplomatic relations between 1873 and 1920. Historian Lorenzo Planzi has studied the period and written a book on his findings. © Armando Dadò, Editore

Your book Il Papa e il Consiglio federale (The Pope and the Federal Council) sheds light on the period from the break in diplomatic relations between Switzerland and the Vatican to their restoration. What led to the rift in 1873?

During the 19th century, relations between Switzerland and the Holy See gradually became more difficult due to the growing conflict between political radicalism and Roman Catholicism. The rift itself took place in the context of the Kulturkampf. In the Etsi multa luctuosa encyclical published on 21 November 1873, Pope Pius IX condemned the discrimination against the Catholic Church by a number of Swiss cantons, which he said had 'subverted all order and uprooted the very foundations of the constitution of the Church of Christ, not only going against every rule of justice and reason, but also violating public duties'. In its meeting on 12 December 1873, the Federal Council decided to break off diplomatic relations with the Vatican, 'considering it of no use to have a permanent diplomatic representation for the Holy See in Switzerland'.

About the person

Lorenzo Planzi was born in Locarno in 1984 and obtained his doctorate in modern history from the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. He coordinated a project for the Swiss National Science Foundation on the history of relations between Switzerland and the Holy See from 1873 to 1920.

But relations didn't break down completely. You mention in your book that informal contacts were maintained. What form did these take?

Over the course of the book it becomes clear that, while there was no shortage of tensions, there were also informal attempts at reconciliation between Switzerland and the Vatican. After the cooling of relations under Pius IX, 1878 marked the beginning of a new papacy under Leo XIII, whose diplomatic approach focused on mediation and led to small but significant efforts at reconciliation. The fundamental first step was the attempt to thaw relations: the Holy See did its utmost to distance itself publicly from the era of Pius IX, while Bern left behind a period of history in which radicalism seemed to have been pushed to its extremes. The second, crucially important step was the effort to seek out and adopt as many measures as possible that might counteract the marginalisation of Catholics in society, from the creation of the University of Fribourg to the election of Joseph Zemp, the first Catholic Conservative federal councillor. The sociopolitical views of subsequent popes and federal councillors also played a vital role in developments.

Come avvenne il riavvicinamento nel 1920 – e quale ruolo ebbe il consigliere federale Giuseppe Motta in questa circostanza?

Al tempo della Prima Guerra mondiale, una convergenza si opera tra la politica neutrale della Svizzera e quella imparziale della Santa Sede. La Santa Sede contatta successivamente il Consiglio federale, per proporre l’ospitalizzazione in territorio neutrale elvetico di prigionieri di Guerra feriti o malati. Berna accoglie la proposta e, grazie all’inedita cooperazione tra Svizzera e Santa Sede, è nel gennaio 1916 che trovano così accoglienza, in terra elvetica, i primi due gruppi – cento francesi e cento tedeschi – di prigionieri tubercolotici. Questa cooperazione umanitaria apre la strada all’invio in Svizzera, sin dal 1915, di un primo delegato ufficioso della Santa Sede, prima della riapertura della Nunziatura a Berna nel 1920. Così, il presidente Giuseppe Motta riesce a convincere i colleghi del Consiglio federale della necessità di riannodare i rapporti ufficiali con il Vaticano.

Where did you conduct your research on the challenges facing bilateral relations between 1873 and 1920?

At the Archive of the Secretariat of State of the Vatican – specifically at the Historical Archive of the Section for Relations with States, whose collection offers a unique insight into the Holy See's perception of the Swiss Confederation over time. I also studied collections at the Vatican Apostolic Archive, as well as the Archive of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Archive of the Pontifical Swiss Guard. I looked at various collections in Switzerland, starting with the Swiss Federal Archives in Bern. To gain a better understanding of the origins of humanitarian cooperation between Bern and the Holy See during the Great War, I followed the advice of the Archbishop of Paris and consulted the archives of the diocese in the French capital. There, I was excited to discover an extensive and previously unpublished correspondence between Cardinal Amette and Switzerland.

Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis writes in the preface that some sections of your book read like a detective novel. What was it like to research? And what surprised you the most?

There are a few pages that certainly are reminiscent of a detective novel. The most pleasant surprise during my research was the European aspect of the rekindling of relations between Switzerland and the Holy See, which was already evident between 1873 and 1920. Informal diplomacy didn't seem predominantly shaped by either Switzerland or the Vatican – that is to say, neither Bern nor Rome was alone in taking the initiative. Instead, it seemed quite European in nature. One need only think of the crucial role played by Paris, which acted as a channel for much correspondence, or the humanitarian cooperation that took place during the Great War.

Did the interruption in diplomatic relations have any specific impact on the relationship between Switzerland and the Holy See?

It's possible that diplomacy needs these moments of coolness and silence, like the one that occurred between Switzerland and the Vatican in the wake of the Kulturkampf, to allow both sides to rediscover the fundamentals of their respective identities. The period of interruption shows each party how unique and valuable their diplomatic relationship really is.